One of the more popular interpretations of the Lulav bundle is that each of the four species represents a different type of Jew based on their possession of Torah or good deeds (Vayikra Rabba 30:12). Specifically:

- The lulav has taste but no smell, symbolizing those who study Torah but do not possess good deeds.

- The hadass has a good smell but no taste, symbolizing those who possess good deeds but do not study Torah.

- The aravah has neither taste nor smell, symbolizing those who lack both Torah and good deeds.

- The etrog has both a good taste and a good smell, symbolizing those who have both Torah and good deeds.

Homiletically, this midrash teaches a message of communal unity. The lulav bundle, also called an “aggudah” (B. Sukkah 33a), represents joining of religiously diverse Jews, presumably towards the service of God. Practically speaking, this message is largely ignored as evidenced by the widespread infighting amongst the divergent Jewish communities.

I suggest that this midrash is not to be taken in isolation. Rather, the homiletic symbolism of the lulav bundle may be understood in conjunction with the corresponding halakhot to provide not only a unique model, but instructions for maintaining a unified Jewish community.

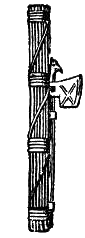

Achieving communal unity is a daunting challenge in that it requires balancing an individual’s identity and freedoms with shared communal goals. One solution to this problem is simply to disregard or eliminate the needs of the individual for the sake of the “greater good.” In ancient times Roman magistrates employed such a system and even used an aggudah of their own to illustrate “strength in unity:”

This type aggudah is called a “fasces” from which we derive the term “Facism.” All participants in this aggudah are identical in appearance showing no signs of individual distinctiveness. As evidenced by the protruding axe, a fundamental characteristic of this aggudah is its dependence on violence. Not only is the “strength” one of physical might, but as history has shown the fascist aggudah typically needs and employs violence to ensure the requisite compliance to conformity.

In contrast, the lulav aggudah requires diversity. Each of the species differs in size, leaves, and number (1 lulav, 2 aravot, 3 hadassim), but more important is how the lulav bundle is formed. Specifically, the lulav must be bound together b’mino – with one of its own kind (B. Sukkah 31a). The common practice is to use leaves from the lulav for both the ties and the elaborate handles. On one hand this is simply pragmatic; the lulav leaves are the most flexible and durable of the three species in the bundle and thus most suited to binding the bundle together.

But remember that according to the above midrash the lulav is representative of Torah. If we allow the metaphor to incorporate halakha we find that what ties most Jews together, especially the marginal ones, is the Torah. Far from forcing rigid conformity, the Torah conjoins the Jews through a degree of flexibility and accommodation. Though there are necessary limits to its malleability – Torah is by no means relativistic – the strength in the lulav bundle’s unity is in its accommodative ability.

Still, the lulav bundle is only 3/4 of the complete set. Explicitly excluded from the aggudah is the etrog (B. Sukkah 34b), signifying the “ideal” Jew with both Torah and good deeds. Here the midrash’s lesson is most relevant for today given the degree of infighting between the religious and more secular Jews, especially in Israel. Unifying the religious and marginalized requires more that a superficial connection of shared history or “Jewish identity.” Rather, just as we must physically bring together the lulav bundle with the etrog, so too the gap between the religious and marginalized Jews can only be mitigated through the active efforts of our own intervention.

Of course this is much easier to accomplish with vegetation than with people, but Sukkot seems to be an auspicious time for encouraging unity. In addition to the midrashic unity of the lulav, the Torah explicitly mandates a national pilgrimage to Jerusalem for a public reading of the Torah called “hakhel” which, while occurring once every seven years, takes places specifically during the holiday of Sukkot (Devarim 31:10-13). Here too, the Jews as a nation are joined together by the common denominator of God’s Torah, but to do so they must first put in the effort as individuals to ascend to Jerusalem in the appointed time.

Perhaps if we today can actualize the lessons of the lulav and figure out how to unify ourselves through the Torah, we will merit the opportunity to come together once again, as a unified nation, at the rebuilt Sukkat David

1. Someone noted that she heard a similar theme from a Rabbi in Dallas, in which case baruch shekivanti. I freely admit that there’s not much of a hiddush here, but it’s a decent standby derasha and I happen to like the analogy.

See second item here:

http://jspot.org/?p=1669#more-1669

Arieh – Thanks for the vid, and yes I did get the title from the Tom Lehrer song.